Culture is the mindset of the firm…it is defined in the Australian Crimes Act as an attitude, policy, rule, course of conduct, or practice. Much of that is embodied in the internal controls of the firm but whether it is documented or not, it is the mindset of the firm[1].

Greg Medcraft

Chair, Australian Securities and Investments Commission

As the (virtual) ink dries on this (virtual) paper, there is shared Australian community outrage at the excessive, extensive and seemingly endemic bad conduct by employees of the major banks and finance houses. However, whilst loss of community confidence in institutions was once seen as the domain of large corporations, loss of community confidence in not-for-profit organisations and institutions is at an all-time high in Australia.

The disturbing public hearings into seemingly endemic abuse over many decades within a great many faith-based and other charitable institutions were not long completed when yet another governance-in-sport issue – this time involving Cricket Australia – caught the public eye in early 2018. This came disappointingly soon after the Australian Sports Commission’s 2016 Governance Reform in Sport report brought hope of governance reforms in that sector. In the meantime, the performing arts reels under revelations of a possible widespread industry culture of tolerance of sexual harassment.

Sadly, today, ordinary citizens, with no previous interest whatsoever in the usually esoteric topic of governance, openly share strong views over their cappuccinos about whether so many boards – both for-profit and not-for-profit – were actually ‘asleep at the wheel’.

The resulting low level of community trust is borne out by research. At the 2018 annual Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD) Governance Summit, the program took as its theme ‘Trust. Sustainability. Innovation.’ Under this banner, AICD chair, Elizabeth Proust, noted in her opening remarks that the global Edelman Trust Barometer[2] results for 2018 showed that Australia and Singapore were the only two countries to suffer a decline in trust across all 4 measured domains of government, media, business and, critically – for the first time – in relation to non-government organisations (NGOs). In all 4 domains trust is at an all-time low in Australia, being below 50% and so is regarded as falling into the category of ‘distrust’. In addressing the need for boards of all kinds – whether ‘businesses’ or NGOs to strive to increase the level of community trust, Proust observed:

What is clear is that the demographic factors – coupled with technological change – have fundamentally altered society’s expectations of their institutions and will continue to do so. Ignoring that will only widen the trust deficit.

…Aggrieved and sceptical communities will question the ‘social licence’ of organisations that lose or exploit their trust. This creates an environment where politicians feel compelled to act, with potentially significant financial, legal and compliance costs.[3]

The establishment and maintenance of trust in a not-for-profit (NFP) NGO starts with the establishment of an organisational culture that is positive. A positive culture might take many forms – for instance it might be a consumer-focused or member-focused culture, a collegiate team culture or a high performing success-oriented culture – but underpinning any positive culture is a strong sense of organisational ethics and values.

This is where the board comes in.

Most boards will readily agree that they have a central role in establishing and maintaining the desired culture. Most, however, will scratch their heads about how they can do so. When things go wrong they will also rightly plead that it is difficult at the least and sometimes even impossible to really know what is going on at the coalface of the organisation if the board is following all of the good governance prescriptions that have guided boards for the past several decades, such as “noses in, fingers out”.

The key question then is this: what can the board do to help maximise the chance of a positive culture and minimise the chances of a poor, destructive or negative culture in their organisation?

What is culture and why does it matter?

As stated at the outset of this article, an organisation’s culture can be thought of as its ‘mindset’. Other formulations include the oft-stated ‘culture is what people do when no-one is looking’ or ‘the way we do things around here’. More formally, as referenced by Greg Medcraft in the opening quote, the Criminal Code Act, 1995 (Cwth) defines corporate culture as “an organisation’s attitude, policy, rule, course of conduct orpractice existing within the body corporate generally or in the part of the body corporate in which the relevant activities takes place”. Yet others talk about organisational culture as the “sum of its share values, principles and behaviours”.[4]

Whatever definition you adopt, the culture of the organisation comprises the values, assumptions, unwritten rules and behaviours that prevail and are commonly accepted in an organisation – the norms – that create the essence of what it is like to work in that organisation. It guides the highest level decisions of the board and management and the minute decisions that its employees make (or don’t make) every day. It becomes deeply embedded over time and can shift significantly but imperceptibly as new employees join the organisation and observe behaviours that appear to be completely acceptable right up to the board and yet may not necessarily align with what is written in the code of conduct and statement of values that were provided to them with on day one.

Organisational culture is perhaps not only the mindset but the very soul of the organisation.

The importance for boards of paying attention to culture is more widely recognised now but it is not a new concept. In the for-profit content, the ASX Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations have long included Principle 3: Act ethically and responsibly. Principal 3 states:

A listed entity should act ethically and responsibly – beyond mere compliance with legal obligations and involves acting with honesty, integrity and in a manner that is consistent with the reasonable expectations of investors and the broader community.[5]

Of more direct relevance to NFP NGOs, Principle 9 (Culture and Ethics) of the AICD Good Governance Principles and Guidance for Not-for-Profit Boards states even more simply:

The board sets the tone for ethical and responsible decision-making throughout the organisation.

Today Australian corporate and prudential regulators, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) and the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA) have published much guidance about the board’s role in setting and maintaining culture leading to the development of a number of useful resources to assist boards to think about this difficult topic. It is perhaps time the charities regulator, Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission (ACNC) did so for the NFP sector. In response to these, publications abound which typically arm boards with the tools and guidance to understand, identify, set, monitor and manage culture.[6] However, it is most important to start with understanding the extent to which the culture or dynamic of the board itself impacts on the organisation.

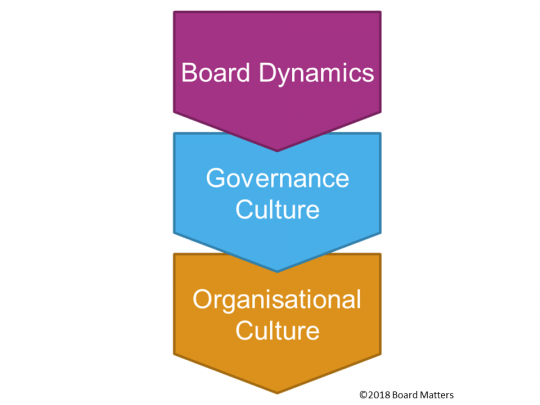

An organisation’s culture is not usually in a single discrete ‘layer’ but rather is something of a multi-layered cake. Depending on their perspective (and even their job within the organisation) some people might for instance be most concerned with, say, the ‘risk culture’ layer or the ‘compliance culture’, the ‘consumer-focused care culture’, the ‘leadership culture’ or the ‘team culture’ layer of the organisation. The cultural layer with which this paper is most concerned can be considered as the top layer of the cake – it focuses on the governance culture of the organisation. The organisation’s governance culture is driven by the values, attitudes and behaviours of the board itself to governance – and even the board’s internal dynamic. The resulting governance culture, in turn, drives or at least heavily impacts the broader organisational culture.

Developing a strong positive culture is especially critical in the NFP sector where employees are often motivated by a desire to be a part of an organisation that ‘does good’ and are easily disenchanted and often lost by organisations that do not live their stated values. The costly and time-consuming matter of staff turnover is one reason alone for paying attention to organisational culture. Funding bodies and donors also demand greater accountability today for their precious resources being put to good purposes by NFPs. When they see a lack of oversight that leads to resources being squandered by poor behaviour, their confidence – and valuable dollars – can be easily lost. The ‘social licence’ of NFP NGOs more broadly might even be at risk if organisational culture is not kept in check; the charitable taxation and other benefits extended to NFP organisations are given as a result of the community’s confidence in the work of NFPs and might just as easily be taken away if that confidence is lost.

In its 2017 not-for-profit governance and performance study[7], AICD reported that the majority of respondents (who are directors serving in non-for-profit organisations) believed that the NFP organisation they serve has a strong, positive organisational culture. The majority of respondents agreed that culture of the board reflects the desired culture of the organisation.

However, many of these respondents recognised their organisation’s lack of formal systems and controls to oversee culture. Nearly half of the respondents indicated that their board does not include culture as part of the board agenda in the past twelve months (52% out of 1,260 directors), and do not receive reports or evaluate KPIs on organisational culture in the past twelve months (48% out of 1,260 directors). Nearly half of the respondents (42%) agreed that their board is passive in overseeing organisational culture. To improve this circumstance, board must take a stronger and more proactive leadership in steering the organisational culture.

Governance leadership: starting with the board’s own culture

So if following good-governance regulatory recipes doesn’t produce good boards, what does? The key isn’t structural, it’s social. The most involved, diligent, value-adding boards may or may not follow every recommendation in the good-governance handbook. What distinguishes exemplary boards is that they are robust, effective social systems.[8]

We have already stated that the organisation’s culture starts at the top with the board. Before looking at some of the tools and practices boards might use to support the development of a positive organisational culture, one of the most important things for the board to focus on is its own culture. Every interaction amongst the board and between board and management is an opportunity for the board to model and embed a positive culture or a negative culture. As the above quote from commentator Jeffrey Sonnenfeld puts it, the exemplary board that establishes such a positive culture is one that can be described as a “robust effective social system”.

The components of the board that can be considered a ‘robust effective social system’ boil down to two simple (but not easy to achieve) concepts:

- A good board enjoys and thrives in a climate of mutual trust, respect and honesty – this is the dynamic both amongst board members and between board and management, which makes for open discussion, debate and constructive dissent; it features board members who can disagree without being disagreeable, with better decision-making being the result; and

- A sense of individual accountability amongst board members – that drives them to take their role seriously, work hard and be present and active in their participation in the meetings and work of the board, even in areas in which they may not be so comfortable (e.g. in the financial governance responsibilities).

Role of the chair in setting culture

Much of the success with which this culture is established will come down to the leadership qualities of the chair of the board and their relationships with board members and the CEO. The role of chair is not to be taken on lightly since the setting of the tone for the NFP board comes in large part from the style and approach of the chair but also involves a great deal of extra time and effort to develop. Just some of the key actions of a chair who sets the right tone are:

- The chair acts as facilitator and conductor of the board, drawing out the people who speak less and pulling back those who speak more but without making them feel stifled or ‘shut down’;

- The chair takes a leadership role, not always leading the conversation but encouraging, supporting and participating in it and ensuring that it reaches a clear conclusion and an explicit decision;

- The chair touches base with board members periodically outside the formal board meeting context to ensure that the chair has the ‘temperature’ of the board, to understand how board members feel about the board, the organisation and how it is tracking;

- The chair spends considerable time in building a strong positive working relationship with the CEO; one that is often best described as ‘friendly but not friends’ and ‘coach and supporter’ characterised by ‘public support but private candour’ – and yet importantly must ensure that this doesn’t come to be seen by the rest of the board as the chair being constant defender of the CEO and ‘in the CEO’s camps’; and

- The chair (and all board members) spend considerable time engaged in the activities of the organisation so that they see for themselves what the culture is really like and don’t only take their information from board reporting and the word of the CEO.

Board/Management relationship and culture

With this tone set by the chair/CEO relationship, of equal importance is the effectiveness of the relationship between the whole of the board and the management team. Some of the actions of boards that set the right tone are:

- The board members are supportive and constructive critics of management – applying the test of friendly fire to management recommendations and reports rather than seeing themselves as the organisational police force – out to catch management out; poor boards can often find themselves in the mindset of looking for the mistakes and trying to catch management out doing the wrong thing, rather than in the mindset of catching management out doing the right thing and calling out credit where it is due;

- The board encourages a culture of openness, transparency and accountability in words as well as deeds; many boards will say that they expect a ‘no surprises’ relationship with management and yet when mistakes or failure are disclosed to them many such boards immediately go into ‘blame’ mode (‘Who is responsible for this? How have we punished them?), resulting in the diametric opposite of what they say they want – a management team that learns not to share bad news but instead tries to bury it in the hope that they can fix it before the board ever finds out;

- Boards that ask themselves regularly what they do that impacts on culture through the board/management relationship they foster at every board meeting; this can be done by including as explicit questions in the regular meeting evaluation questions:

- What did we do at today’s meeting that encouraged management to tell us the bad news as well as the good news?

- What discussions did we have today that focused on the culture of the organisation? Which discussions could have been more culture-focused?

- Boards that develop and adhere to a board charter that reflects all of these preferred behaviours and forms the platform for the board’s annual performance evaluation gives management the confidence that the board is as much interested in its own performance management and continuous improvement as they are in the performance management and continuous improvement of management.

Practices and tools for promoting, supporting and maintaining positive culture

A range of practices, tools and structures can also be used by the board and management to help ensure that consideration of culture is embedded in all aspects of the organisation. Drawing on a number of sources, suggestions include:

- Encouraging and facilitating open conversations at board level on the values of the organisation – if the board is not part of that conversation it is doubtful that they can ever hope to live and model the values that are expected of others;

- Developing or adapting a formal code of conduct and ethical standards – but also ensuring that we check regularly to see that these standards are lived and not just platitudes;

- Making it safe to challenge undesirable practice and behaviour – what ‘good people’ will tolerate is often regarded as setting the behavioural standards even if those same people do not agree with the behaviour they observe;

- Undertaking team-building exercises – the stronger the level of trust and confidence amongst the team, the more likely it is that some of the prior listed practices will be supported and enabled;

- Training and support – when people join the organisation and regularly thereafter, including when poor practices are identified, training and support is provided to help promote deeper understanding of the desired practices and behaviours of the organisation;

- Reviewing hiring and firing practices – ensuring poor behaviour discouraged without also encouraging a culture of ‘burying mistakes’;

- Changing how success is rewarded/celebrated – albeit more of a problem in the for-profit sector many organisations have been found to have adopted remuneration and incentive policies and approaches that encourage behaviours that are contrary to the organisation’s stated values and expectations;

- Consider the value of including culture measures or indicators in the board’s regular reporting – whilst caution is recommended in accepting ‘culture diagnostic tools’ that profess to give board and management a definitive view of the organisation’s culture, some indicators on the board’s regular ‘dashboard report’ can (subject to the next point) give at least useful lag indicators and in some cases lead indicators of good or bad culture, such as results of staff climate surveys, member or consumer satisfaction surveys and other such results;

- Notwithstanding the value of the indicators (prior point), there is no substitute for board members being engaged in the activities of the organisation to really understand its culture much more deeply than any dashboard report can ever do – attending events, getting to know staff and stakeholders in order that stakeholders have enough confidence to approach board members if ever the whistle needs to be blown and even just to given ongoing positive and negative feedback that helps the board ensure the organisation is on track; and

- Pay attention to the many statements (values statements, codes of conduct, risk appetite statement) that impact on culture and, as discussed in the final section below of this paper, consider whether there is a place for an overarching ‘culture statement’ that pulls each of those together.

Developing a ‘culture and risk appetite statement’

A firm’s corporate culture permeates all aspects of its business, including attitudes towards risk-taking, customer treatment, competence, compliance with rules, innovation, plain speaking, diversity and inclusion, empowerment of staff to make decisions, and the time horizon over which costs and benefits are considered.[9]

The past two decades has seen a heavy focus on the development by boards of a range of key ‘statements’ that serve to define what they expect of themselves, of management and through management of the rest of the organisation. In particular over the past decade, the emphasis has been on the development of ‘risk appetite’ statements for organisations. Such a statement is designed to clarify what sort of risks it is acceptable and unacceptable to take with the financial and other resources of the organisation and, most important of all, with its reputation.

Perhaps a missing piece for many organisations over the past has been the overarching statement about culture and what is expected behaviourally within the organisation. Whilst this is partly found in many organisations in the values statement, the code of conduct and employment policies it is suggested that it is timely to consider consolidating all of these statements together into an overarching Culture Statement. Such a statement, adopted by the board, should make it clear that the values, code of conduct and risk appetite statement come together under this umbrella to create a culture that is expected to be lived.

It is conceivable that the Code of Conduct for an organisation is already such a document, setting the cultural parameters and expectations. If so, whilst it is undesirable to create yet another separate document, the board should ensure that the document makes explicit that it is designed to set a positive culture, rather than being a punitive document designed to catch out bad conduct. This more punitive connotation is often seen as the real purpose behind the ‘code of conduct’. Hence a Culture Statement (and Code of Conduct) that makes explicit the purpose of the document to set a positive culture is a great step forward.

Of course, the last piece in the puzzle is that the board and management regularly check that the Culture Statement is lived and is not mere platitudes. Just like the Values Statement, the Code of Conduct, the Risk Appetite Statement, the board’s own charter, the organisation’s strategy, if the Culture Statement sits in a drawer (or even in a frame on the wall) gathering dust and is not embedded in performance management, regular reporting and the old fashioned ‘sense check’ that comes from seeing how things work on the factory floor, its development will have been a waste of time and scarce resources.

After all, as a leading Australian company director recently said following a governance crisis arising out of the discovery of a widespread organisational culture of exploiting workers, the most important thing for board members in order to be satisfied with the culture of their organisation is to ‘walk around in the shadows of the boundaries of the business’.

It is time for NFP directors to take a walk in the shadows of the boundaries of their business as we strive to rebuild community trust in our social licence to operate.

Elizabeth Jameson

Reference:

[1] Korn Ferry Institute, The tone from the top: Taking responsibility for corporate culture, p31

[2] See Edelman Trust Barometer published by public relations firm Edelman at http://cms.edelman.eom/sites/default/files/2018-02/2018_Edelman_Trust_Barometer_Global_Report_FEB.pdf

[3] See Opening Address: Australian Governance Summit – Trust, Innovation and Sustainability by Elizabeth Proust at https://aicd.companydirectors.com.au/events/australian-governance-summit/latest-news/opening-address-ags-2018

[4] See Managing Culture – a good practice guide (First Edition), p9 published by The Ethics Centre at http://www.ethics.org.au/SJE/media/Documents/managing-culture-a-good-practice-guide-2017.pdf

[5] See ASX Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations (Third Edition) published by ASX Corporate Governed Council at https://www.asx.com.au/documents/asx-compliance/cgc-principles-and-recommendations-3rd-edn.pdf

[6] See Managing Culture – a good practice guide (First Edition) published by The Ethics Centre at http://www.ethics.org.au/SJE/media/Documents/managing-culture-a-good-practice-guide-2017.pdf

[7] See 2017 NFP Governance and Performance Study published by Australian Institute of Company Directors at https://aicd.companydirectors.com.au/~/media/cd2/resources/advocacy/research/pdf/06017-5-nfp-governance-and-performance-study-2017-amended-web.ashx

[8] Sonnenfeld, J What Makes Great Boards Great, Harvard Business Review, September 2002

[9] See Management information on culture – Connecting the dots published by Deloitte Centre for Regulator Strategy at https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/sg/Documents/financial-services/sea-fsi-management-information-on-culture-noexp.pdf